Types of Hosting and How They Differ

Choosing a hosting solution is one of those decisions where mistakes rarely show up right away. At the beginning everything may work just fine, but as the project grows you can suddenly run into slowdowns, instability, functional limitations, or unexpected costs. In most cases the issue isn’t a “bad provider,” but the fact that the chosen hosting type doesn’t match the real needs of the project.

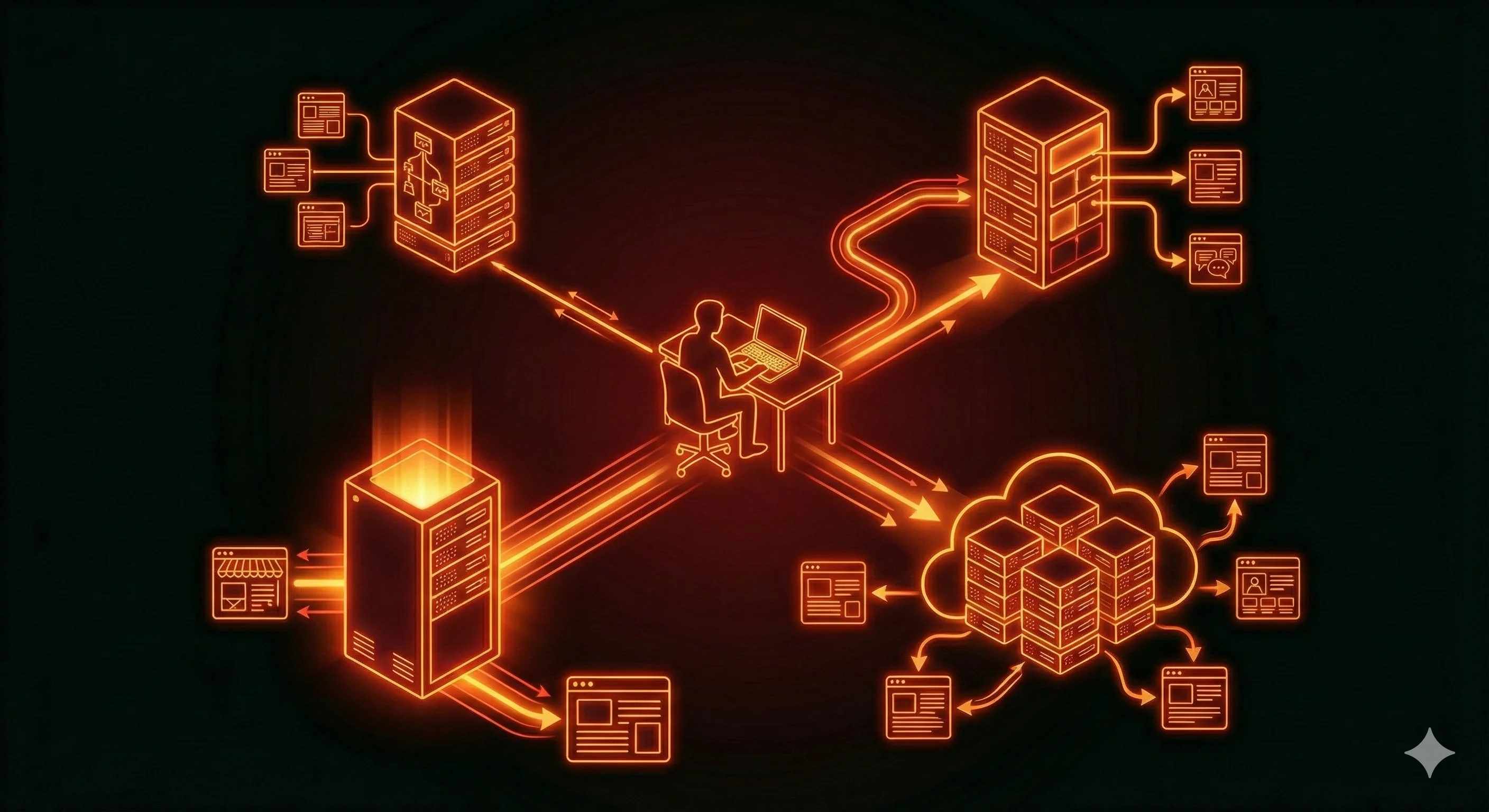

Shared hosting, VPS, dedicated servers, and cloud solutions are not steps on a “worse–better” ladder. They are different models of how resources, responsibilities, and risks are distributed. To make a conscious choice, it’s important to understand how each model actually works and what limitations are built into it from the start.

Hosting from an infrastructure perspective

At a basic level, any hosting is a computing environment where your website or application code runs. Regardless of the plan, the same core components are always involved:

-

Physical server or server pool — the actual hardware in a data center.

-

CPU — processing power that determines how quickly requests are handled.

-

RAM — memory for applications, cache, and background processes.

-

Storage — files, databases, logs, and backups.

-

Network — bandwidth, latency, and connection stability.

The differences between hosting types come down to three key aspects:

-

how these resources are shared between customers;

-

which resources are guaranteed and which are provided on a “best effort” basis;

-

who is responsible for configuration, updates, and security.

In general, the cheaper and simpler the hosting, the less control the user has and the more dependent they are on the provider and other customers.

Shared hosting

Shared hosting is the most common option for small websites. The core idea is simple: one physical server hosts many projects at the same time. All sites run within the same operating system and use a standardized software environment configured by the provider.

The user interacts with the server through a control panel and has no access to the system level. This is a deliberate limitation — the provider trades flexibility for simplicity and scalability.

From a resource perspective, shared hosting has several fundamental characteristics:

-

no guaranteed CPU or RAM — resources are allocated dynamically;

-

strong dependence on “neighbors” — one site’s load can affect others;

-

strict functional limits — restrictions on cron jobs, background tasks, sockets, queues.

Shared hosting works well if the project meets certain conditions:

-

traffic is relatively small and stable;

-

the site doesn’t perform heavy computations;

-

a standard stack is used (PHP + MySQL, popular CMS);

-

there are no requirements for custom services or system-level settings.

Typical use cases include corporate websites, blogs, landing pages, simple portfolios, and small online stores without complex logic.

It’s also important to be aware of the limitations that often become apparent later:

-

you can’t install your own versions of system libraries;

-

you can’t run persistent background processes;

-

real-time functionality is difficult or impossible to implement;

-

scaling usually means migrating to a different hosting type.

VPS

A VPS (Virtual Private Server) is a virtual machine running on a physical server. Unlike shared hosting, resources here are allocated in advance and reserved for a specific user.

Each VPS comes with:

-

its own operating system;

-

a guaranteed amount of CPU and RAM;

-

dedicated disk space;

-

network isolation from other VPS instances.

From a technical standpoint, a VPS is very close to a physical server. The user has root access and full control over the environment: they can install any packages, configure web servers, databases, queues, caching, and load balancing.

A VPS is considered a universal solution for most mid-sized projects. It’s well suited for:

-

online stores with real commercial traffic;

-

backend applications and APIs;

-

sites with non-standard stacks;

-

projects that are actively growing and evolving.

At the same time, a VPS requires administrative knowledge. With an unmanaged VPS, the owner is responsible for:

-

OS and package updates;

-

firewall and SSL configuration;

-

backups;

-

monitoring and incident response.

Managed VPS plans reduce this burden but cost more and still leave architectural decisions in the user’s hands.

Dedicated server

A dedicated server means renting an entire physical server. All of its resources belong to a single client, with no virtualization and no competition for hardware.

The main advantages of this approach are:

-

stable, predictable performance;

-

no virtualization overhead;

-

maximum hardware isolation;

-

the ability to use specialized equipment.

Dedicated servers make sense when a project has consistently high load or specific requirements. Common examples include:

-

large SaaS platforms;

-

high-traffic online stores;

-

systems handling large volumes of data;

-

projects with increased security requirements.

Cloud hosting: moving beyond a single server

Cloud hosting changes the very approach to infrastructure. Instead of running on a single server, a project operates on a distributed system where resources are drawn from a shared pool.

Key characteristics of the cloud model include:

-

Horizontal scaling — adding new nodes as load increases;

-

Vertical scaling — changing resources without stopping the service;

-

Fault tolerance — failure of one node doesn’t bring the system down;

-

Pay-as-you-go pricing — you pay only for what you actually use.

The cloud is especially effective in these scenarios:

-

unpredictable or seasonal traffic;

-

rapid project growth;

-

microservice architectures;

-

requirements for high availability.

At the same time, cloud solutions demand a more mature approach. Architecture becomes more complex, and automation, monitoring, and cost management play a much bigger role. Without solid DevOps experience, cloud projects often suffer from budget overruns and unnecessary complexity.

A practical approach to choosing

It makes sense to choose hosting based on current needs, not on hypothetical future scenarios. In practice, the logic usually looks like this:

-

a simple site with no growth — shared hosting;

-

a commercial project or growing load — VPS;

-

consistently high traffic — dedicated server or cloud;

-

unpredictable load and scaling needs — cloud infrastructure.

The key principle is to avoid overengineering. Complex infrastructure is justified only when it solves a specific problem. Otherwise, it increases costs, complicates maintenance, and slows down development.

Hosting is a tool, not a goal. It should match your current requirements, be easy to manage, and allow you to scale when it actually becomes necessary.